Why equalising the age of consent mattered

In 2001, a landmark moment for equality took place in the UK. The Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act came into effect, finally granting gay and bisexual men the same age of consent as heterosexual people. This change wasn’t just legal, it was symbolic. It told the country, that gay relationships were not different, lesser, or shameful.

Before this, the law set the age of consent for gay men at 18, two years higher than for heterosexual couples. It carried a powerful message that gay and bisexual men were less trustworthy and less mature. But the law didn’t just stigmatise them, it turned their very existence into a crime. For young gay men, it meant that simply being themselves, having consensual relationships at the same age their straight peers could, made them criminals.

This was the tail end of a long and painful history of criminalisation. The Labouchere Amendment of 1885 had made “gross indecency” between men a criminal offence, punishable by up to two years’ imprisonment. A glimmer of hope appeared in 1957 with the Wolfenden Report, which recommended that “homosexual behaviour between consenting adults” should no longer be a crime, setting the proposed age of consent at 21. A decade later, the Sexual Offences Act 1967 decriminalised sex between men in England and Wales, but only for those over 21, and only in private. Sadly, persecution persisted long after.

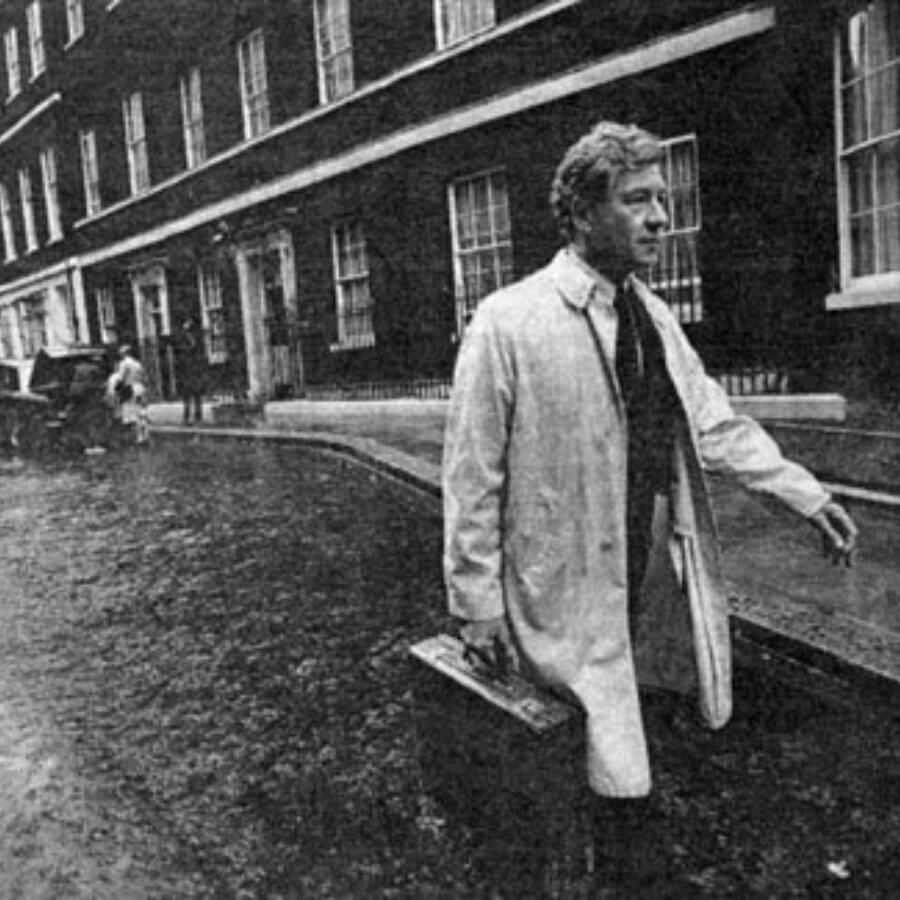

One of Stonewall’s founders, actor Ian McKellen, powerfully captured why the fight for an equal age of consent mattered “We shall hear, once more, that boys mature later than girls and need the law to protect them from what may be only ‘a homosexual stage’.

McKellen went on to highlight the deeper harm of inequality, “We will be told that young men should continue to be dissuaded from homosexuality because gay men lead such unhappy and unstable lives. Those of us at ease with our sexuality are neither unhappy nor unstable. Those gay men who have difficulty with their sexuality suffer greatly because of the discrimination they face, which starts with the unequal age of consent.”

The equalisation of the age of consent in 2001 wasn’t just about those two years, it was about justice and an acknowledgment of what the law had denied. It marked a crucial step toward a society that values everyone’s right to love and be loved without shame or fear.

The work of Stonewall, among others, in the long fight for equality

But equality before the law didn’t come easily. Getting the law changed took years of campaigning. Organisations like Stonewall, along with MPs and activists, worked tirelessly to make progressive change. Again and again, the proposal was voted down in the House of Lords. The legal change required the Government to enact The Parliament Acts, which allows for the elected House of Commons to bypass the House of Lords in order to pass legislation into law. This was a rare move that showed just how strongly people believed this change needed to happen.

As much as this was a legislative battle, it was about saying that every young person, gay or straight, deserves to grow up knowing their love and identity are just as valid as anyone else’s.

The wider impact

The equalisation of the age of consent, paved the way for the repeal of Section 28 in 2003, the introduction of civil partnerships in 2004, and eventually marriage equality in 2013. It was one of the first big signs that the country was moving towards greater acceptance.

Today, it’s easy to forget how recent that inequality was. But remembering it helps us see how far we’ve come, and how much perseverance it took to get there. In these turbulent times, we are reminded yet again that hard won rights are not always secure, but in courage and unity, is hope.